INTRODUCTION

The quality of finished surfaces plays a crucial role in industries such as mechanical engineering, automotive, aerospace, and others. Surface quality directly impacts the performance, reliability, and longevity of products. Common surface defects include roughness (micro-irregularities from processing), waviness (periodic variations in surface height), cracks, stains, and inclusions.

This article aims to revisit previously published findings, emphasizing the importance of integrating self-learning capabilities into defect detection systems. Such systems, built on modern artificial intelligence principles, offer significant potential beyond traditional supervised learning approaches. However, a review of existing methodologies reveals that many current defect detection techniques fail to deliver practical, industry-ready results for modern mechanical engineering applications. Overreliance on artificial intelligence methods without adequate integration of classical mathematical statistics and engineering principles has led to unrealistic expectations regarding their scientific and practical outputs. These classical approaches retain their value and continue to provide robust solutions.

Bodies of rotation (BR), such as spheres, cylinders, cones, and torus shapes, are fundamental to many precision applications. Rotational components like aircraft bearing balls, precision steel balls, and cylinders (Fig. 1) are critical in industries such as aviation, railways, and precision machinery. The performance and durability of these parts heavily depend on the surface quality, requiring manufacturers to adhere to rigorous precision standards.

Advanced quality control systems are indispensable for detecting and addressing surface defects, ensuring that components meet the high-performance demands of their applications. By combining modern Al-driven techniques with proven statistical and engineering methodologies, defect detection can achieve both innovation and practical relevance, enhancing product quality across diverse industries.

The earlier results were published in the article [25], presented at the XXVI International Symposium Research-Education-Technology, held in Stralsund on September 26th–27th, 2024.

Different approaches to surface quality analysis are described in [1]. This research includes a variety of methods that can be applied in different industrial contexts. The solution of the problem of modeling quality analysis is not only theoretical [2–3], but also of great practical importance [4–5]. Practical applications of these methods include quality control in manufacturing processes, where even the smallest deviations in surface quality can lead to defects that compromise product performance and durability. Probably, one of the first approaches to the construction of automata for detecting defects in the surface of bodies of revolution is the simulation of training and work of a human operator [6–8]. Operators can recognize defects after becoming familiar with a small number of different objects of the same type. A person has an amazing ability: having become acquainted with a small number of different objects of the same class, he subsequently recognizes all the objects of this class. Within the framework of the work [6], surface defects are considered as statistical anomalies of roughness parameters. To detect them, the degree of homogeneity of the surface quality is determined and compared with the permissible threshold value [13]. Such a method makes it possible to effectively identify anomalies, which is key to ensuring high product quality.

In recent years, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has revolutionized surface defect detection. Advanced algorithms [15] can now analyze complex patterns in surface data, enabling the identification of defects that were previously undetectable using traditional methods. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [16] have been employed to classify surface imperfections with high accuracy, reducing reliance on manual inspection and increasing efficiency in production lines.

Moreover, the application of deep learning techniques has facilitated the development of automated inspection systems capable of real-time defect detection. These systems utilize large datasets to train models that can discern subtle variations in surface textures, leading to more reliable quality control processes [17]. Additionally, the use of transfer learning [18] has shown promise in situations where limited defect data is available, allowing models to leverage knowledge from related domains to improve detection performance.

The adoption of non-contact measurement techniques, such as laser-based methods, has further enhanced surface quality analysis. These approaches offer high precision and are less prone to damaging delicate surfaces compared to traditional contact methods [19]. Furthermore, the implementation of 3D scanning technologies combined with ML algorithms [20] has enabled comprehensive assessments of complex geometries, providing detailed insights into surface integrity. Recent advancements also include the use of digital holographic microscopy for surface topography measurements. This technique allows for high-resolution, three-dimensional imaging of surfaces, facilitating the detection of micro-scale defects that may impact product performance [21]. Additionally, the development of hybrid models that combine statistical methods with machine learning approaches has improved the robustness of defect detection systems [22], making them more adaptable to varying manufacturing conditions.

The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) devices with surface inspection systems has opened new avenues for real-time monitoring and predictive maintenance. By collecting and analyzing data from connected sensors, manufacturers can proactively address potential quality issues before they escalate, thereby reducing downtime and associated costs [23].

Furthermore, the standardization of surface measurement techniques, as outlined in ISO 25178, has provided a unified framework for assessing surface texture, ensuring consistency and comparability across different industries and applications [24]. This standard encompasses both contact and non-contact measurement methods, reflecting the diverse approaches employed in modern surface analysis.

In conclusion, the convergence of advanced technologies such as AI, machine learning, and non-contact measurement techniques has significantly enhanced the field of surface quality analysis. These innovations have led to more accurate, efficient, and reliable defect detection methods, ultimately contributing to improved product quality and manufacturing efficiency.BR roughness parameters are statistically homogeneous along the angular coordinate, so defects are identified as statistical anomalies of these parameters depending on the BR rotation angle for each point on the symmetry axis. This means that any anomalies in roughness can be detected by analyzing deviations from the norm at different angles of rotation. The surface equation (1) of some defect-free BR in a cylindrical coordinate system (ρ, φ, z) (Fig. 2) is a one-dimensional nonnegative function S independent of φ. This means that the BR surface is symmetric about the z-axis and does not vary with the angle φ. With this symmetry, the analysis of the BR surface becomes simpler, as it is sufficient to study changes in one dimension.

where: z – axis of symmetry BR; ρ – radius BR; S – defined function.Surface defects can be represented as a two-dimensional variable function, i.e., as noise (2): This approach allows for more precise defect modeling and analysis, since the noise can represent a variety of surface inhomogeneities. By analyzing the characteristics of this noise, different types of defects can be more accurately identified and classified.

where: φ - rotation BR.With this approach, the BR surface equation (3) forms that describes its physical structure and properties in the context of the application under study. This is a key element of the analysis that enables accurate modeling and simulation of BR surfaces under various operating conditions.

Assume that a parallel beam of light falls on the BR surface at an angle whose aperture is larger than the allowable size of the defects. In this case, defects on the BR surface will be easier to detect because they will cause light scattering. By analysing the pattern of this scattering, the size and location of defects can be precisely identified and measured. The intensity of the reflected beam at a certain point in space for a BR without defects can be described by a one-dimensional non-negative function fs, which does not depend on the angle φ (4). This means that the distribution of reflected light intensity on the BR surface is uniform along the angular coordinate φ, which simplifies the analysis and interpretation of the measurement results.

In contrast, for BRs with defects, the intensity of the reflected beam is a two-dimensional non-negative function (5). In this case, the analysis must consider the rotation of the BR depending on both the angle φ and the variation of the reflected intensity along the entire z-symmetry axis of the BR to accurately identify and characterize defects. This reflects the complexity and irregularity of the surface due to the presence of defects.

which after discretization takes the form (6): end; end;where: I – number of counts per one rotation turn BR, J – number of counts by length BR, zmax – BR length.

Let us estimate the moving average of intensity Di, j as (7):

where: K – the size of the sliding window (the period of the moving average), |i + k|I – modulo I addition operation.To reduce calculation time, recurring formulas are used (8):

Equation (8) introduces a recursive method for computing the moving average of intensity mi, j significantly reducing the number of operations required for data analysis. Instead of summing the intensity values within the window K at each step, the new average is computed based on the previously calculated value mi–1, j, by adding the newly acquired sample Di, j and removing the oldest sample D|i – k|i, j. This approach reduces the computational complexity from O(K) to O(1), which is particularly advantageous for large datasets. As a result, it enables a faster and more efficient analysis of reflected light intensity, making it especially beneficial for real-time processing or extensive measurement datasets. Ultimately, this method optimizes computational performance while maintaining the same level of accuracy as the traditional moving average calculation.

ESTIMATING THE DISPERSION OF THE MOVING AVERAGE

Let us determine the RMS1 measurements of Di, j according to the expression (9) [14–15]:

The coefficient of variation (CV) is a commonly used quantity that is equal to the ratio of the standard deviation of a random variable to its mathematical expectation. It is used to compare the variation of the same attribute across several aggregates using different arithmetic means (10).

Let us define the average value of the moving dispersion volatility2 vavi, j as (11)

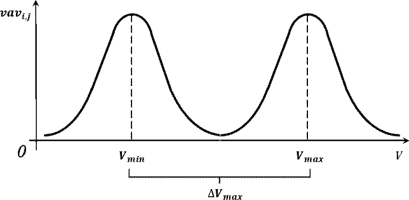

For a deep understanding of the statistical properties of the BR flow, it is desirable to construct a distribution function vavi, j, which, as a rule, takes the form (12).

If vavi, j ≥ Vmax then go to

Figure 3 illustrates the discriminant function for deciding whether there is a surface defect in the body of revolution based on the difference value of the maxi, j – mini, j.

Fig. 3.

Distribution function of the variability vavi, j : Vmin – minimum acceptable value of sliding dispersion variability; Vmax – maximum acceptable value; ΔVmax – uncertainty range introduced for borderline classification cases; vavi, j – difference between local maximum and minimum coefficient of variation within the sliding window

THE DECISIVE RULE OF DEFECT DETECTION

This rule (13) is based on the coefficient of variation (CV), a statistical measure that quantifies fluctuations in signal intensity across multiple sampling points. By leveraging this approach, the system effectively classifies surface conditions into three categories: defective, acceptable, or requiring further training.

The decision-making process relies on a threshold-based framework, where the maximum permissible variability, denoted as Vmax, acts as a critical limit for defect detection. This threshold is determined experimentally to ensure optimal sensitivity in identifying structural anomalies. Additionally, an uncertainty zone, ΔVmax, is introduced to account for borderline cases where classification remains inconclusive. In such scenarios, the system requires further adaptation to refine its diagnostic accuracy, reducing false positives and false negatives.

The algorithm operates iteratively, processing samples along both the axis of symmetry and the rotation angle of the examined surface. The variability index, vavi, J, is computed as the difference between the maximum and minimum CV values within a predefined analysis window. If vavi, j exceeds Vmax, the system classifies the corresponding region as defective, assigning it to the defect class

This structured approach significantly enhances classification accuracy by integrating an adaptive learning mechanism that continuously evolves based on new defect patterns. Unlike traditional methods that rely on fixed thresholds, this system dynamically improves over time, ensuring greater reliability in detecting even subtle irregularities. By employing statistical analysis and machine learning-based adaptation, the model optimizes its diagnostic precision, reducing the reliance on manual inspection and increasing automation efficiency.

The implementation of this decision rule holds substantial implications for industrial applications, particularly in sectors where precision and defect detection are paramount, such as aerospace, automotive, and high-precision manufacturing. By minimizing human intervention and optimizing defectoscopy workflows, this methodology paves the way for a more robust, scalable, and intelligent quality control system.

for

for

for

13

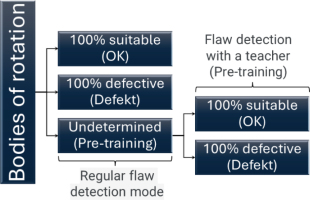

That is, the BR input stream is divided into three groups of products (Fig. 4), while the "Undetermined (Pre-training)” group is used to retrain the flaw detector with a teacher (human operator).

Fig. 4.

The input stream of bodies of revolution (BR) is classified into three categories: suitable (OK), defective (Defect), and undetermined (Pre-training). The undetermined group serves as an experimental base for additional supervised training. This classification allows the system to iteratively refine the decision boundary between suitable and defective BR through feedback-based adaptation

The result of the work (13) is the division of the input flow from N BR into three groups of products: 100% suitable

Let us adjust the average value of the moving volatility dispersion vavi, j and Vmax (14-15):

14

Based on (14), it is necessary to adjust the value of Vmax (15):

Let’s adjust the average value of the moving volatility dispersion ΔVmax based on 100% suitable (OK) (16):

16

Based on (16), it is necessary to adjust the value of ΔVmax (17):

That is, in this way, the range of additional values is determined ΔVmax.

DISCUSSIONS

The training of the machine in the process of its operation (Pretraining) is carried out by the operator, who selects defect-free BR from among the undefined BR and feeds them to the input of the machine in the training mode. Automatically, the system corrects Vmax and ΔVmax. Ensuring high accuracy in determining these parameters is a top priority. The probability of convergence to optimal values can be close to one with unlimited additional training time. However, the number of iterations required for convergence increases over time almost linearly, while accuracy increases logarithmically with the number of iterations.

External correction is carried out by the "teacher". Both a human operator and an automaton can act as a "teacher". In our case, the teacher is a human operator. It is based on the processing of control (a posteriori) information that the missing initial information is filled. While training, the automatic system accumulates experience, based on which the necessary reaction of the system to external influences is gradually developed. A learning automatic system is an asymptotically optimal system, since its optimal response to external disturbances is not achieved immediately, but over time, as a result of training.

In the self-learning mode, each BR assigned by the automaton to the class (OK) generates a parameter refinement Vmax and ΔVmax. The operation of the machine in self-learning mode is periodically monitored by the operator, who selectively checks small batches of BR from classes (OK) and (Defect) and decides whether additional training of the machine is necessary. A self-learning system is a self-adjusting system, the algorithm of which develops and improves in the process of self-learning. This process comes down to trial and error. The system makes tentative changes to the algorithm and simultaneously monitors the results of these changes. If the results are favorable from the point of view of management goals, then changes continue in the same direction until the best results are achieved or until the management process begins to deteriorate.

Machine vision-based methods overcome the low accuracy and low throughput of manual (visual) detection and are widely used in a variety of industrial applications, including the inspection of steel strips, aluminum profiles, and optical components. Images of steel surfaces contain a lot of noise caused by lighting problems, pseudodefects (artifacts), etc. Surface defects, their types, and characteristics vary greatly. A wide range of methods are used to detect defects, both in the spatial and frequency domains. Often, a combination of several methods produces useful results. Recently, neural networks or neural network-based methods have been used to classify defects.

One of the main directions of development of modern mechanical engineering is the creation of the so-called "intelligent engineering" based on computerized integrated production, modern computer equipment, software control and special-purpose software, the main goals of which are:

– Optimization of production processes using machine learning algorithms.

– Improveement of BR quality with computer vision and deep learning.

– Design and development automation that reduces the development time of new BR and allows engineers to focus on more creative tasks.

All of this is significantly transforming the process, providing new opportunities to optimize BR design, manufacturing, and quality management.

We would like to pay special attention to the problem of end-to- end simulation of defect control of bodies of rotation based on CAD/CAM/CAE systems. The key link in such production is numerical control machines, which provide not only automatic processing of workpieces but also the creation of control programs, the generation of design documentation based on geometric two-dimensional and three-dimensional modeling using CAD modules of integrated systems, and the development of the technological process by means of SAM.

To solve these problems, finite element control of surface defects of the rotation body type was simulated using DEFORM 3D and ANSYS. Simulation of the numerous physical properties of the reflection of electromagnetic waves from the surface of the rotation body leads to the solution of linear or nonlinear equations, or partial differential systems of equations. In some cases (Fourier analysis, series decomposition, etc.), solving problems in a general way, is impossible without the use of numerical methods. With the growth of computer performance, numerical simulation is of particular importance, as it allows for the replacement of direct physical experiments.

The DEFORM 3D Finite Element Method (FEA) software package is based on the simulation process of a system designed to analyze a variety of forming processes used in metal processing, such as extrusion, broaching, upsetting, pressing, rolling, drawing, and allows for a comprehensive analysis of metalworking—from the operation of sectioning rolled products into billets to the operations of final machining, control of geometry, and surface defects of bodies of rotation.

It should be noted that both convolutional neural networks (CNN) and holographic methods represent promising directions in the development of surface defect detection systems for rotational bodies. CNNs are capable of high-accuracy classification based on visual data, while holography offers detailed, high-resolution surface profiling. However, both approaches remain under active research and development and may require extensive data, complex setups, or specialized conditions for reliable industrial deployment.

CONCLUSIONS

This study presents a statistical approach to the automated detection of surface defects on highly reflective, rotationally symmetric bodies. The proposed method is based on the analysis of reflected light intensity and its statistical variability across the surface, using a sliding dispersion window. Defect detection is achieved through a threshold-based classification rule that leverages the coefficient of variation (CV) to distinguish between defective, acceptable, and uncertain surface regions.

A key feature of the system is its self-learning capability. In the “Pre-training” mode, samples with uncertain classification are reintroduced into the training process under human supervision. This allows the system to refine its classification parameters (Vmax and ΔVmax) based on verified defect-free bodies. Over time, the system asymptotically approaches optimal performance through repeated iterations and feedback.

Although the methodology is well-formulated and supported by statistical reasoning, practical experimental results—such as real-world surface images, classification accuracy, or defect detection rates—are not included in the current study. These will be addressed in a follow-up publication, which is expected to cover the full implementation and empirical validation of the system.

In summary:

– The method integrates classical statistical techniques with adaptive learning to create an effective defect detection system.

– The decision-making rule based on sliding dispersion variability enhances the robustness and interpretability of the classification.

– Human-assisted self-learning ensures that the system continuously improves its performance with minimal manual intervention.

– The described solution has promising applications in industries requiring high-precision surface control.

A relatively detailed description of the end-to-end modeling system for monitoring surface defects of bodies of rotation is beyond the scope of this article and is expected to be published in the third part of the author’s trilogy on this topic. Future work will also focus on the experimental validation of the proposed approach, including performance benchmarking, integration with machine vision hardware, and comparison with existing AI-based defect detection systems.